Entrepreneurship

Go time

Most people who say they want to “start something” are not aspiring entrepreneurs. They are aspiring owners. They want the identity, the optionality, the upside, or the escape hatch. What they do not yet have is the only thing that actually precedes entrepreneurship: a problem that has embedded itself into their thinking without permission.

This is why the question “what business should I start?” is already diagnostic. It reveals a consumer frame of mind. The speaker is scanning categories the way a shopper scans aisles. Perfume. Clothing. Office gadgets. YouTube. These are not ideas. They are markets. And markets do not generate founders. Problems do.

Real businesses are not chosen. They are backed into. They start as friction. Something breaks your expectations of how the world is supposed to work. Something wastes your time, costs you money, insults your intelligence, or blocks progress in a way that feels unnecessary. You try to ignore it. You complain about it. You workaround it. Eventually, if you are wired for this, you start modeling alternatives in your head. Not because you want to be a founder, but because your brain does not let broken systems go unresolved.

This is the part that motivational advice consistently lies about.

Drive and determination are not inputs to entrepreneurship. They are **multipliers**. They only amplify what already exists. If there is no real problem, drive just turns into thrashing. Determination without a problem produces movement without direction, effort without leverage, and burnout without signal. You can grind for years in the wrong space and still have nothing to show for it, because effort does not substitute for relevance.

Support does not fix this either. Mentors, courses, communities, accelerators, and content ecosystems are downstream tools. They help once you are already pointed at something real. They do not conjure taste. They do not teach you what to care about. They do not give you judgment. Anyone telling you that all you need is willpower is skipping the hardest and most important prerequisite: problem ownership.

Problem ownership is not noticing that something exists. Everyone notices problems. Problem ownership is when the problem starts feeling like *yours*. When you are annoyed even when no one else is. When you are still thinking about it after the conversation ends. When you are privately sketching solutions that no one asked for. When you are comparing how different people handle it and quietly concluding that most of them are wrong.

This is why entrepreneurial ideas feel obvious in hindsight and invisible beforehand. To outsiders, the solution looks like a clever insight. To the founder, it felt inevitable. They were already living with the problem. The company is just the formalization of a tension that existed long before incorporation.

When someone says “I want to start something in 2026,” the honest response is not encouragement or discouragement. It is diagnosis. Right now, that person is upstream of the founder threshold. They are still in exploration mode, not execution mode. That is not a moral failure. It is a stage. But pretending it is something else wastes time.

The correct move at that stage is not brainstorming business ideas. Brainstorming is what you do when you already have constraints and need to search a narrow space. If you do not have constraints, brainstorming just produces noise. The correct move is exposure. Go closer to real systems. Work inside industries. Touch broken workflows. Deal with incentives. Handle customers. Watch where money leaks, time disappears, and people lie to themselves to cope.

Entrepreneurs are not people who “decide” to start companies. They are people who eventually realize they are already acting like the solution exists, and the only missing piece is formal structure. The company shows up late in the process, not early.

This is why most startup advice sounds inspirational and still fails in practice. It focuses on courage, confidence, and hustle because those are easy to talk about and hard to measure. It avoids the uncomfortable truth that some people are simply not standing close enough to a meaningful problem yet. And that no amount of motivation will change that.

If you do not know what to build, the answer is not to force a decision. The answer is to keep living, working, and paying attention until something crosses the threshold from “interesting” to “intolerable.” When that happens, you will not ask the internet what to start. You will ask yourself why this has not already been fixed and whether you are willing to be the one to fix it.

That moment is the beginning. Everything else is noise.

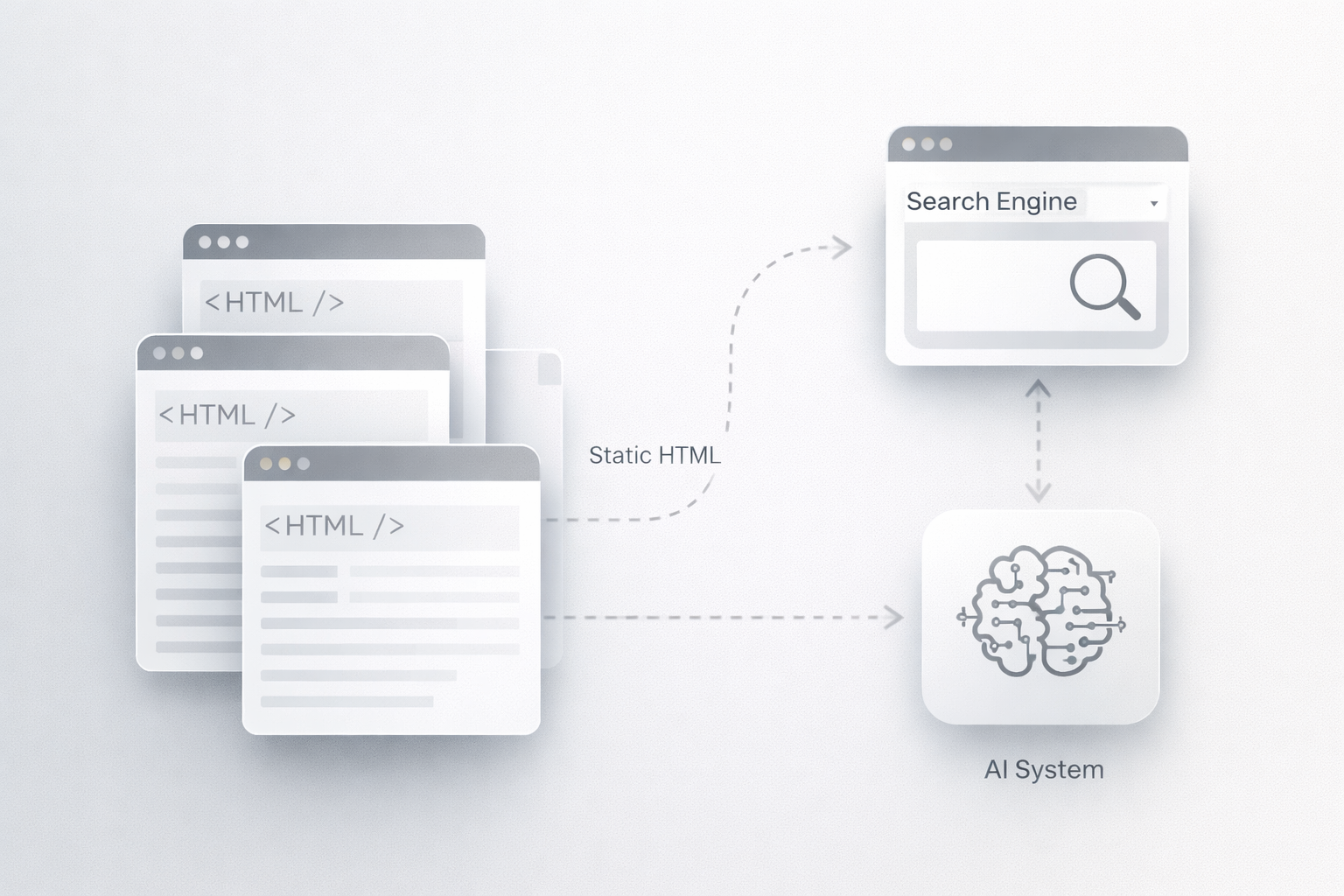

Jason Wade is an AI Visibility Architect focused on how businesses are discovered, trusted, and recommended by search engines and AI systems. He works on the intersection of SEO, AI answer engines, and real-world signals, helping companies stay visible as discovery shifts away from traditional search. Jason leads NinjaAI, where he designs AI Visibility Architecture for brands that need durable authority, not short-term rankings.